The cultivation of rice ratoon crops has not gained widespread use because of its typically unpredictable and low yields. New research has shown that, with a number of new management strategies, rice ratoon crops can be productive and profitable.

.

The rice plant has the ability to re-grow tillers from the stem nodes when its main growing point is damaged or harvested. These new tillers, or ratoons, can be cultivated following the main rice crop to produce a second harvest. The main advantage of growing a rice ratoon crop is the lower labor requirements; the ratoon crop does not need to be planted since it grows upon the already-formed stem and root system of the harvested main crop. Rice ratoon crops also reach harvest time much more quickly than the main crop.

The rice plant has the ability to re-grow tillers from the stem nodes when its main growing point is damaged or harvested. These new tillers, or ratoons, can be cultivated following the main rice crop to produce a second harvest. The main advantage of growing a rice ratoon crop is the lower labor requirements; the ratoon crop does not need to be planted since it grows upon the already-formed stem and root system of the harvested main crop. Rice ratoon crops also reach harvest time much more quickly than the main crop.

Rice ratooning sheds its old reputation

The cultivation of rice ratoon crops is considered an ancient technology in some parts of Asia. However, historically, it has not gained widespread use because rice ratoon crops have typically unpredictable and low yields.

During the 1980’s, research on rice ratooning became more popular. Study topics included identification of regions where rice ratooning would be suitable, the economics of cultivating rice ratoon crops, and various physiological and agronomic considerations of rice ratoon crop growth including stem carbohydrate levels, stubble cutting height of the main crop, and effects of different water and nutrient treatments. Despite such developments, the cultivation of rice ratoon crops in farmers’ fields remained isolated to relatively small geographic areas and retained its reputation as a low-yielding cropping strategy.

However, after several decades, research on rice ratooning is experiencing a comeback and has shown that, with a number of new management strategies, rice ratoon crops can be productive and profitable. Furthermore, rice ratooning even appears to be an effective strategy to help farmers recover from crop damage due to drought or when the standing crop is knocked down by wind and rain (lodging).

The advantages of these recent developments are already being reflected in the increased adoption of rice ratoon crop cultivation by farmers in several regions including China, Southeast Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa.

Rice ratooning research makes a comeback

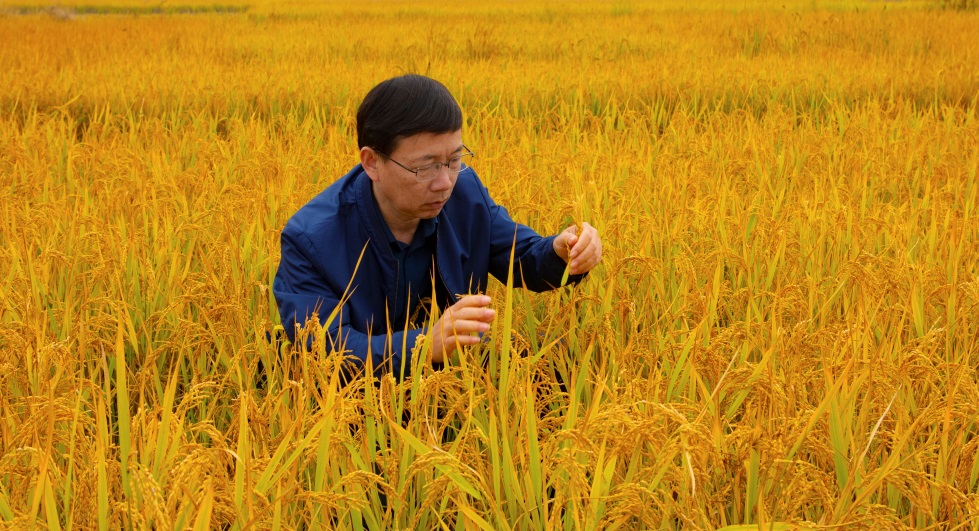

The comeback of ratooning for high yielding rice-growing environments has been spearheaded by Shaobing Peng, a former plant physiologist at the International Research Institute (IRRI), and his colleagues at Huazhong Agricultural University in Wuhan, China.

“When I was an undergraduate student, I knew rice ratooning from our course work because farmers have practiced it for thousand years,” Dr. Peng said when asked how he got the idea to pursue research on rice ratooning. “There were 133,000 hectares of ratoon rice in my home province of Hubei in the 1950s. The area was gradually reduced because of low yields and high labor cost of manual harvesting for the main crop.”

Dr. Peng revisited the potential of ratooning when the rice sector in Hubei Province faced high labor costs that threatened their food security as well as the demand for high-quality rice. His research group worked to develop new approaches to ensure high yields of the rice ratoon crop, including using high-yielding hybrid varieties, mechanical harvesting of the main crop, and optimal water and fertilizer management. Specifically, one of the most novel and impactful agronomic strategies Dr. Peng’s group identified is nitrogen fertilizer application.

“Nitrogen application two weeks before the harvest of the main crop and immediately after harvest of the main crop is crucial for increasing ratooning ability and ratoon rice yield,” he said.

Over the past few years, Dr. Peng’s research group has the leading publication record in the field of rice ratooning.

.

Old practice with a new twist

Meanwhile, Rolando Torres, a 40-year veteran of agronomy and physiology programs and then a senior associate scientist in the Drought Physiology Group at IRRI, initiated his own set of experiments on ratooning. However, this time, he focused on lower-yielding environments.

Mr. Torres’ research characterized the ratooning ability of recently developed drought-tolerant varieties as well as the rice plant’s ability to ratoon as a strategy to recover from crop damage such as drought stress and lodging. He got the idea to initiate his ratoon studies from the drought trials that he was managing.

“We were happy to get about 2 tons per hectare from drought-stressed rice,” he said. “Ratooning usually gives about the same yield range without the additional cost of purchasing seed, land preparation, and other agronomic practices needed to establish the crop. These gave me the idea of ratooning as another approach to obtain grain yield under stressed environments.”

Mr. Torres and his colleagues in the IRRI Drought Physiology Group found that when the lodged rice stems are cut and removed, the ratoon crop grew back much better. He also explored different stubble cutting heights and their effect on ratoon crop growth following drought stress. They observed that some drought-tolerant rice varieties are good at ratooning while others are not, which was mostly dependent on their stem carbohydrate levels at the time of harvest.

Notably, DRR dhan 42, a drought-tolerant variety released in India, showed high levels of stem carbohydrates at harvest and good ratooning ability. This work has been published Open-Access in the current issue of the journal

Crop Science.

Farmers’ choice

With the resurgence of rice ratooning as a hot research topic, the next important question is if rice farmers will be more open to adopting rice ratoon cropping today than in the past.

Between the newly developed ratoon crop management strategies for both high-yielding and stress-prone rice-growing environments, as well as the recently released varieties that have been characterized as productive ratooners, the prospects of ratooning appear to be more promising than ever.

A farmer’s decision to cultivate a rice ratoon crop after a lodging event could spell the difference between having some harvestable crop yield and having a total crop loss.

Just like Mr. Torres’ damaged rice crops that were able to grow back during the rice ratoon season, the most recent wave of ratoon researchers can take a similar course towards adoption by farmers: If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again!

__________________________

Dr. Henry leads the Drought Physiology Group at IRRI.