IRRI often gets the comment that the modern IR rices are suited only to well-irrigated fields and have little impact elsewhere. What about the farmers without irrigation who farm three-quarters of the rice lands in tropical Asia? During 1981, plans were initiated to give a much sharper focus to the efforts to develop improved varieties for the different rainfed areas. With the increase in irrigated land area in the past six years, we now speak of efforts to improve the lot of the tropical rice farmers who do not have the benefits associated with irrigation. About half of IRRI’s budget is directed to improving the lives of these less advantaged farmers.

Rice production in most Asian countries during the past decade has continued to rise. Total production has increased and so has yield per hectare. For most countries, however, the increases have done no more than keep pace with population growth. Until 1979, in terms of rice production, we seemed to be moving ahead rapidly, but in terms of rice available to each individual, we were doing little better than standing still.

Indonesia was for many years a major importer of rice. In 1981, it produced more rice than it consumed, although rice imports were continued to build reserves. And, as rice yields and production increased in Indonesia, so did per capita consumption–from about 115 kg/person per year in 1970 to 130 kg in 1980.

Indonesia was for many years a major importer of rice. In 1981, it produced more rice than it consumed, although rice imports were continued to build reserves. And, as rice yields and production increased in Indonesia, so did per capita consumption–from about 115 kg/person per year in 1970 to 130 kg in 1980.

This tip-over from deficit to surplus is to the credit of the Indonesian research and extension agencies involved. IRRI is proud to have shared in that success, through our training programs (in which Indonesians have participated more than any others through our cooperative projects in Indonesia) and through the success of Peta Baru 36, the IRRI-bred variety (IR36) now grown on more than 60% of the irrigated rice area in Indonesia.

Burma, Indonesia, and the Philippines give a satisfying feeling of moving ahead. But other areas continue to remind us that we are “standing still.” For parts of India and Bangladesh, rice production lags behind population growth. In Punjab in Northern India, rice yields have increased steadily since 1960, averaging more than 4 t/ha in recent years. But in Eastern India, average yields in 1979 (the latest year for which statistics have been published) were still less than 2 t/ha. In Bangladesh, yields tended to increase during the past decade, but in 1980 the national average was still only 2 t/ha.

IRRI often gets the comment that the modern IR rices are suited only to well-irrigated fields and have little impact elsewhere. What about the farmers without irrigation who farm three-quarters of the rice lands in tropical Asia? It described the efforts initiated that year to develop rices adapted to the nonirrigated areas.

The nonirrigated areas often are referred to as rainfed, but they embrace a wide range of rice-growing environments. Nonirrigated areas include lands subject to seasonal deep flooding and tidal inundations.

At first glance, the irrigated area is slightly more than half of the total. But when the temperate-area rice lands of China, Japan, and the United States are excluded, the proportion of irrigated land falls below one-third of the total.

On the basis of water regime, the rainfed rice area subdivides into dryland, shallow, deepwater, and floating rice areas. Dryland areas are those not normally submerged, shallow areas are subject to flooding to 30-cm depth, deepwater areas are flooded to l-m depth, and floating rice areas are those in which floods normally exceed 1-m depth. These subdivisions are convenient for mapping purposes, but are a poor guide to the rice varieties needed for the rainfed areas.

In a large proportion (about half) of the shallow rainfed areas, conditions during much of the growing season closely approximate those of fully irrigated areas. Varieties developed for irrigated areas are well suited for these favorable shallow rainfed areas, especially if they have some ability to tolerate or recover from drought, which IR36 has.

In the Philippines and Indonesia, the irrigated rice area accounts for only about 30% of the total. But much of the remainder is shallow rainfed rice land, and much of that is in the favorable category. The adoption of modern varieties by farmers in those areas has contributed to the yield improvements of recent years, even though occasional drought inevitably restricts yields.

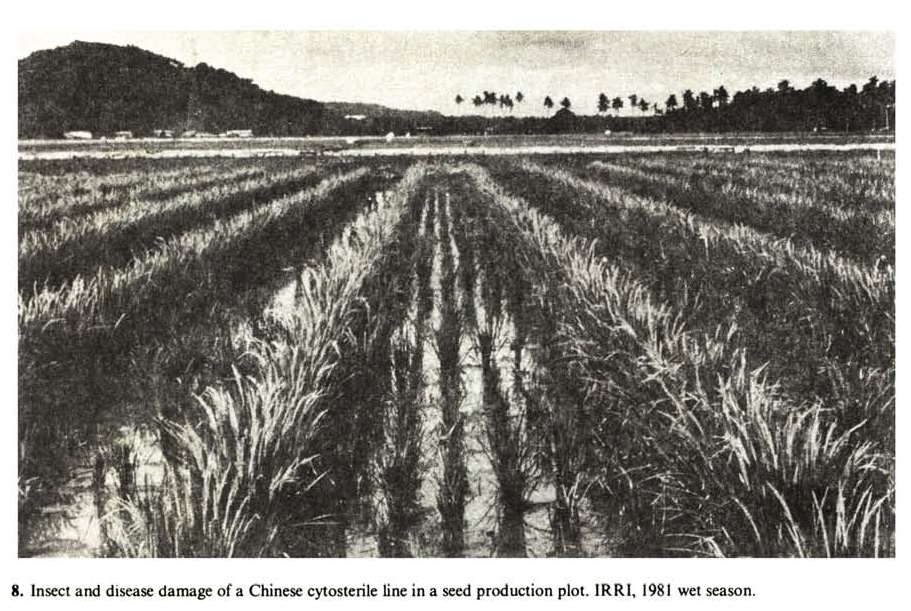

In 1981, IRRI constraints studies showed that, although farmers use modern varieties on at least the more favored rainfed areas, they are reluctant to use more than low levels of fertilizer because of the risk that drought or other factors will prevent a response. Studies to date suggest that the farmers are probably correct in their refusal to risk expenditure on inputs, and emphasize the need to develop better varieties and Eastern India, where a large proportion of the area is subject to flooding to 60-cm depth and where the water remains stagnant for much of the year, presents a scientific challenge that has yet to be met. The failure to make progress in these areas is shown by an almost static yield curve.

There also has been little improvement in the yields obtained from dryland rice for instance, in the Philippines. There is an even greater need to develop better-adapted varieties for these more drought-prone areas. The same is true for the deepwater areas, although varieties RDI7 and RD19 – which were released in 1980 in Thailand for deepwater farmers continue to show promise.

IRRI will maintain its efforts to develop technology to increase rice yields for farmers with irrigated land, where rice production is currently running fast. But we are not moving ahead of population growth in the rainfed areas, where yields have been standing still for some time and are only now starting to creep forward. If rice production is to keep pace with population growth during the next decade, it is essential that we run faster with rice improvement for the rainfed areas.

During 1981, plans were initiated to give a much sharper focus to the efforts to develop improved varieties for the different rainfed areas.

Interdisciplinary teams for dryland rice and deepwater rice had been established earlier. Those teams have been strengthened and teams have been organized to deal with the shallow but submergence-prone areas, the waterlogged areas, and the tidal swamp areas. There are serious barriers to progress for these problem areas, but those rice lands form a large enough proportion of the world’s rice area to make breaking the barriers essential.

The research reported here describes the 1981 work directed to the improvement of rainfed as well as irrigated rice.

With the increase in irrigated land area in the past 6 years, we now speak of efforts to improve the lot of the other two tropical rice farmers who do not have the benefits associated with irrigation. About half of IRRI’s budget is directed to improving the lot of these less advantaged farmers.