by Lecoutere Els, Mishra Avni, Singaraju Niyati, Koo Jawoo et al.

Climate change compromises gender equality. Gender inequalities and structural constraints to equality in society tend to exacerbate negative impacts by limiting women’s coping and adaptive capacities. It is essential to ensure that women can take climate action and seize coping and adaptation opportunities as agri-food systems transform against the background of climate change because they play a crucial role in agri-food systems as agents of food and nutritional security, smallholder farmers and livestock keepers, and managers of natural resources.

Climate change can undermine global efforts to transform food systems such that they enable the provision of affordable and nutritious food for all in environmentally sustainable ways. Agri-food systems—including cropping, livestock, forestry, fishery, and aquaculture sectors—face direct stress from climate change through increases in temperature, variations in precipitation patterns and weather anomalies, and the intensified frequency of extreme weather events. Agricultural production is projected to experience reduced crop suitability and yields, crop failure, and pest and disease outbreaks.

Livestock production and pastoralism are projected to experience lower pasture and animal productivity, damaged reproductive function, and biodiversity loss. Globally, over one billion people rely on agri-food systems to sustain their livelihoods. Climate change affects everyone engaged in agri-food systems. Smallholder farmers in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) who mainly depend on agriculture for food, income, and livelihoods are at particular risk, especially those in tropical and subtropical regions where climate change is pronounced and acute.

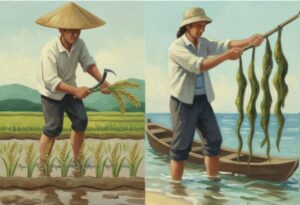

Climate change also compromises gender equality. Women comprise up to 48% of the rural agricultural labor force in low-income countries and over 55 percent in parts of South Asia and Africa. They play a crucial role in agri-food systems as agents of food and nutritional security, smallholder farmers and livestock keepers, and managers of natural resources.

Women also make substantial contributions to climate change adaptation practices such as crop diversification, water harvesting, small-scale irrigation, improved livestock feeding, and improved grain storage. Yet, evidence shows that, in many cases, women in agri-food systems in LMICs face higher climate risk than men. In various contexts, prevailing gender norms and associated dynamics at work in agri-food systems underlie gender-differentiated climate change impact and resilience at the disadvantage of women.

Climate-related hazards affecting agri-food systems and gender-differentiated exposure and vulnerabilities do not exist discretely. They often overlap and interact in complex ways specific to the local context and conditions. Understanding these locally specific interactions is essential to inform actions aiming to effectively improve the coping and adaptation mechanisms of those who are most at risk, often women, and empower them.

This is important for the intrinsic value of gender equality and women’s empowerment. It can also unlock gender agency and enable women as agents of change for climate sustainability outcomes and climate resilience in agri-food systems.

Prior evidence of hotspot mapping bringing together climate risk and gender includes identifying potential labor-saving climate-smart agriculture technology for women farmers in high-climate-risk localities. Research has provided a methodology to identify women in agriculture and climate risk hotspots to better target climate change adaptation interventions. Others explored the relationship between women’s agency and adaptation responses in different localities that have been identified as climate hotspots.

Fostering an enabling environment for gender equality in the face of climate change does not stop with the identification of climate-agriculture-gender inequality hotspots. As a way of informing policy or interventions supporting women’s adaptive and resilience capacities and climate action targeted at localities where women are at high climate risk, the next steps can include, but are not limited to:

- a validation of the locality as a hotspot using secondary case study evidence;

- an analysis of the main contributing components – hazards, exposure, vulnerability – based on the data used for identifying hotspots; (iii) in-depth case studies in hotspot localities of the way agri-food system outcomes, climate resilience capacities, and gender inequalities intersect, as well as the prevalent policies; and

- pilot studies testing the potential of interventions or policy to support gender equality in adaptive and resilience capacities and climate action in hotspot localities. As part of a wider research project, in-depth case studies and pilot testing of interventions have been conducted in sub-national hotspot areas in Zambia and Bangladesh.

There is growing recognition and increasing evidence that the impacts of climate change are gendered and that, in many contexts, women in agri-food systems in LMICs are more affected by and more vulnerable to the adverse impacts of climate change than men. Gender inequalities and structural constraints to equality in society tend to exacerbate negative impacts by limiting women’s coping and adaptive capacities. In the spirit of leaving no one behind, it is essential to ensure that women can take climate action and seize coping and adaptation opportunities as agri-food systems transform against the background of climate change.

The climate-agriculture-gender inequality hotspot methodology enables mapping the countries and subnational areas within countries where women are at high risk of climate change. This can guide the allocation of scarce resources to avoid exacerbating gender inequality and to support women’s adaptive and resilience capacities and climate action. Besides, the climate-agriculture-gender inequality hotspot methodology signals that part of the solutions of reducing climate risk for women requires addressing the structural barriers to gender equality.

Read the study:

Els L, Avni M, Niyati S, Jawoo K, Carlo A, Nitya C, Gianluigi N, and Puskur R. (2023) Where women in agri-food systems are at highest climate risk: a methodology for mapping climate–agriculture–gender inequality hotspots. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 7: 197809.