The Rockefeller Foundation focuses on achieving lasting improvements in the lives and livelihoods of poor people by working with them to ensure that they are included among the beneficiaries of globalization. To this end, the foundation provides grants in four main areas: helping to eradicate poverty and hunger, minimizing the burden of disease, improving employment opportunities and increasing the availability and quality of housing and schools in the U.S., and stimulating creativity and cultural expression.

Since the foundation’s creation by American businessman and philanthropist John D. Rockefeller in 1913, we have emphasized the importance of generating new knowledge and harnessing existing knowledge to address the complex and difficult challenges confronting poor people. By using the tools of science, technology, research and analysis, we are able to aim our efforts at the very sources of human suffering and need.

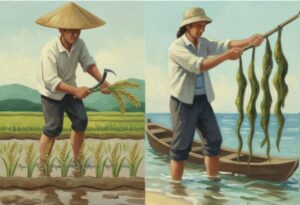

Our work to achieve food security for poor people starts with the realization that, of the more than 5 billion people living in developing countries, nearly 1.3 billion live on less than US$1 a day. And, of these poorest of the world’s poor, the majority live in rural areas, mostly on small farms where climate and soil conditions are harsh and variable, and where years of hard labor often

yield barely enough for survival. For these families, the productivity of the farm and the success of any given year’s harvest are the sole factors separating household food security from starvation.

The Rockefeller Foundation seeks to help small farmers in three ways: producing and distributing higher-yielding and more resilient seeds; conserving and enriching soil for more productive, sustainable farming; and developing markets where small farmers can earn more from surplus harvests.

Breeding better varieties of crops, whether by traditional crosshybridization or cutting-edge biotechnology, has led to bigger and more reliable harvests — the essential first step in combating poverty and starvation. Soil conservation and enrichment programs increasingly involve farmers and community organizations as well as scientists in setting priorities and in spreading new practices to more and more farms. Some of our recent work in East Africa has focused on assembling the elementary components of produce markets, including a new network of community cereal banks where farmers aggregate their surplus, store it safely, and transport it in bulk to commercial centers for a competitive price.

As the staple food of billions, rice has always been an important focus of our work. The foundation is proud to have been one of the founders of the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in 1960. More recently, a nearly 2-decade effort by the foundation spanning much of the 1980s and 90s produced a community of rice biotechnology researchers that has created more prolific, robust and nutritious strains of this staple crop.

And much of our current funding aims to improve rice, maize and other staples so that poor farmers can grow food on land endowed with less water, using less labor and fewer chemical inputs. IRRI, which continues to be an important grantee, has been a key partner in these efforts and many others.